Valsalva-Stuttering Blocks Revisited

In persistent developmental

stuttering (the most common form of stuttering in adults and teenagers),

the actual �block?occurs in the brain before the person who stutters even

tries to say the word. The block is an error in the neurological

motor programming of the larynx to phonate the vowel sound of a

specific word or syllable.

Before

any bodily movement can occur, the brain must first create a motor

program to determine when and how muscles are to be activated. The

same is true for speech. A neurological process called prephonatory

tuning must prepare the appropriate muscles in the larynx to bring the

vocal folds together at the proper time to vibrate as airflow passes

between them. The vibrating vocal folds create a buzzing noise. The buzz

is turned into specific vowel sounds by the shape of the oral cavity, as

determined by the position of the lips and tongue.

Before

any bodily movement can occur, the brain must first create a motor

program to determine when and how muscles are to be activated. The

same is true for speech. A neurological process called prephonatory

tuning must prepare the appropriate muscles in the larynx to bring the

vocal folds together at the proper time to vibrate as airflow passes

between them. The vibrating vocal folds create a buzzing noise. The buzz

is turned into specific vowel sounds by the shape of the oral cavity, as

determined by the position of the lips and tongue.

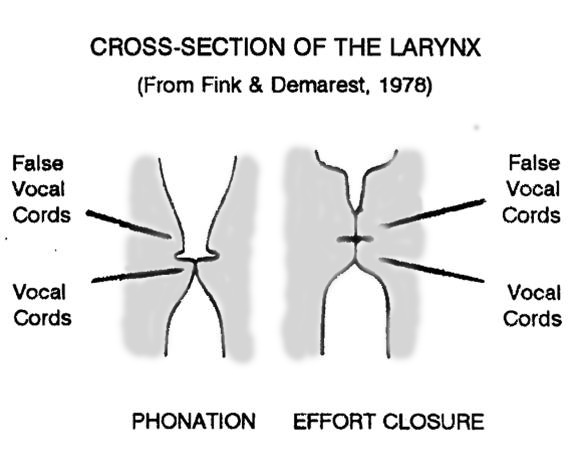

When the person who stutters

comes to the word or syllable in question, the brain does not program the

larynx to phonate the vowel sound. Instead, the larynx is programmed for

effort closure ?the function that it performs during a Valsalva

maneuver. For that reason, we will call these blocks

�Valsalva-stuttering blocks.?nbsp; The vowel sound is the natural place

for motor programming for effort to occur, because it is the part of the

syllable that is loudest and therefore has the most energy.

In effort closure, the

entire larynx closes tightly ?including both the vocal folds and the

false vocal folds above them ?to keep air from escaping. The purpose is

to build up air pressure in the lungs to stiffen the trunk of the body, so

that physical effort can be exerted more efficiently. Often the person

who stutters will feel tightness in the throat as well as the abdominal

muscles. Even if the larynx does not actually close, it still is not

ready to play its part in saying the vowel.

The rest of the speech

mechanism ?the lips and tongue ?must now wait until the larynx is ready

to phonate the vowel sound. The person�s speech gets stuck on the

consonant or glottal stop that precedes the vowel, resulting in

repetitions, prolongations, hesitations, and/or forceful closures of the

mouth or larynx. This creates a false impression that the initial sound

is causing the problem.

It should be noted that a

stutterer�s lips and tongue usually have no trouble articulating words on

their own, when they don�t have to wait for the larynx to phonate. For

example, a person who stutters is almost always fluent when there is no

phonation, as in whispering, or when phonation is continuous, as in

the �Humdronian Speech Exercise?or singing.

The person who stutters may

feel as if the feared word contains an insurmountable obstacle ?often

described as a �brick wall??that requires force to overcome. The PWS

may be overwhelmed by a seemingly uncontrollable urge to use physical

effort to force the word out ?as in a Valsalva maneuver. This may

instinctively feel like the right thing ?the only thing ?

to do. But the more the speaker builds up air pressure to break through

the perceived block, the stronger the block becomes.

The

Block Is an Illusion

In reality, there is no

obstacle or �brick wall.? It is an illusion, with no substance or power

of its own. Its only power comes from you.

You yourself create the

obstacle by exerting effort in trying to force through it. That is the

essence of a Valsalva maneuver. The blockage of the upper airway

automatically becomes stronger to resist the air pressure that you build

up in your lungs. The purpose is to stiffen the trunk of the body to help

you exert physical effort more efficiently. This maneuver is totally

inappropriate for speech. You may feel as if you are b eing

conscientious by �trying hard,?but you are creating the very obstacle

that you are struggling against.

eing

conscientious by �trying hard,?but you are creating the very obstacle

that you are struggling against.

A well-known example of this

principle is the Chinese finger trap. A person inserts an index

finger into each end of a woven bamboo tube and then tries to free them.

The instinctive reaction is to pull the fingers outward, but the harder

the person pulls, the tighter the tube becomes. The victim ends up

trapping himself by his own effort in trying to escape.

Stuttering Blocks and Anxiety

Valsalva-stuttering blocks

are associated with varying degrees of anxiety, as illustrated in the

following diagram. The degree of anxiety may affect a block�s resistance

to therapy.

Low-Anxiety

Blocks

High-Anxiety Blocks

The �Speech

Alarm System?/span>

The �Speech

Alarm System?/span>

As discussed in

The Neurological Triggering

of Stuttering Blocks, the triggering of stuttering blocks is similar

to the sympathetic nervous system�s �fight-flight-freeze?response to

fearful stimuli. The purpose of this response is to keep us safe by

causing our bodies to react instantly and automatically to potential

danger. This reaction is initiated by the almond-shaped amygdalae

?the parts of the brain in which fearful memories are stored. (There

is one amygdala in each hemisphere.)

The amygdalae�s sensitivity

to stimuli may vary, depending on the situation. For example, if you were

strolling through a safe, quiet neighborhood during the day, your

amygdalae would probably be on a low alert level, allowing you to think

pleasant thoughts and enjoy yourself. In contrast, if you had to walk

through a crime-infested neighborhood at night, your amygdalae would

probably be on high alert for muggers. Any movement in the shadows might

cause them to send an alarm ?triggering the release of stress hormones

through your brain and body.

Likewise,

the triggering of stuttering blocks may vary greatly, depending on the

speaking situation. We might better understand this variance if we view

it in terms of a ?b>Speech Alarm System.?/span>

Likewise,

the triggering of stuttering blocks may vary greatly, depending on the

speaking situation. We might better understand this variance if we view

it in terms of a ?b>Speech Alarm System.?/span>

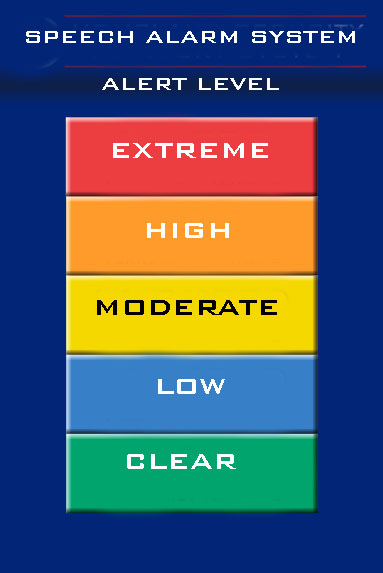

We will visualize the Speech

Alarm System as having the following color-coded �Alert Levels?

As you enter speaking

situations, you may habitually set the sensitivity of your �Speech Alarm

System?based on your memories, thoughts, expectations, attitudes, and

beliefs about the difficulty or danger of the speaking situation and/or

the words you anticipate saying.

The following is a

hypothetical example of how the Speech Alarm System might work. This

process may be conscious, unconscious, or semi-conscious. It may seem to

you as being so necessary, automatic, and inevitable that you feel you

have no choice in the matter.

Your amygdalae are now on

Extreme Alert for the dreaded �p-words?(or whatever other type of word

you might fear). As you come to a �p-word,?your amygdalae send out an

alarm: �Danger! Danger!?nbsp; This triggers your sympathetic nervous

system to initiate the fight-flight-freeze response, which floods your

brain and body with stress hormones.

These hormones cause your

larynx to be neurologically programmed to do effort closure instead

of phonating the vowel sound of the specific word or syllable. (Doing

effort closure as part of a Valsalva maneuver is an instinctive way to

prepare your body for physical action.) The stress hormones also shut

down the thinking part of your brain, causing you to forget everything you

may have learned in speech therapy. You instinctively revert back to your

old, established struggle or avoidance behaviors ?as if no other choices

are possible. All the while, the stress hormones are urging you to

�Force! Force!??as if you were in real danger and needed to fight off a

mugger.

But there is no mugger. It

is only a word. You are safe. Your Speech Alarm System has given you a

false alarm. Because speaking situations present no real dangers,

all of its alarms are false alarms.

The Speech Alarm System is

actually unnecessary and counter-productive. Nevertheless, you keep using

it because, on some psychological level, it helps you feel safe.

You might feel naked and exposed ?and perhaps even terrified ?without

it. Exerting effort in response to the alarms set off by your amygdalae

has the immediate short-term effect of reducing your anxiety. Over the

long term, however, responding to these false alarms perpetuates your

fears and stuttering behaviors.

Back to top.

Copyright ?2012 by William D. Parry

![]()